Sequence

Lindsay Anderson co-founded the influential film journal Sequence with Peter Ericsson in 1947 when they were studying at Oxford. The first issue was financed by the Oxford University Film Society and contained Anderson’s ‘Angles of Approach’. Although the Oxford University Film Society decided not to fund any further issues Anderson and Ericsson decided to continue with Sequence, the next few issues being financed by Anderson. As both Ericsson and Anderson had left Oxford by this point and were based in London they moved the writing and editing of the magazine to Gavin Lambert’s spare room and Anderson invited Lambert to be a co-editor. Sequence continued as a film quarterly until 1952.

Click here for past issues of Sequence

The following text is an edited version of an introduction for a proposed re-print of Sequence written by Lindsay Anderson in 1991. It was originally published on the Stirling University Archive website and is reprinted here by kind permission. Anderson’s introduction provides a valuable insight into the outlook of the magazine and its creators and puts Sequence in its historical context. It also provides an account of Free Cinema and the films which followed.

Sequence: Introduction to a reprint

I have often asked myself why I should find it so difficult – almost impossible – to write an introduction to this reprint of SEQUENCE, which was published intermittently over a period of five years or so, and went out of business over forty years ago. The magazine was in many ways a renowned success. However, as the advertising agent we visited in 1950 told us, our chances were those of “Snowballs in Hell”. He was quite right. After all, we were hoping to attract advertisers (and no periodical that is not subsidised, like Screen or Sight and Sound, could possibly survive without advertising) to a British quarterly review of Cinema that was determinedly uncompromising, specialist and personal, serious and humorous, enthusiastic and well-informed. It is sobering to think that no magazine with these qualities can hope to survive in Britain.

SEQUENCE flourished in the late forties and early fifties. It was a forerunner. Five years after it ceased publication there came Hungary and Suez and the New Left. On the home scene there appeared Free Cinema and the Universities and Left Review. The English Stage Company took possession of the Royal Court Theatre and presented “Look Back In Anger”. The Angry Young Men and all they signified were a journalistic invention, yet they marked a change, almost a revolution, in British cultural and social life. The hectic sixties followed, with all their venturesomeness and variety.

It has become fashionable to deride that turbulent decade for its extraordinary mix of “progressive” politics, of impatience with fossilized structures, of anarchism and flower-power, of drugs, meditation and Pop. We should not forget that the mix had certain ingredients whose loss has proved terribly damaging: most notably vitality and hope. Also a great deal more humour that its critics appreciate, or possess themselves. From the late sixties it was downhill all the way. The seventies substituted profit for experiment. Squabbles in the Labour Party ate away at the Socialist Ideal. The unions became increasingly sectarian, increasingly materialist, until they deserved as well as received their defeat at the hands of Margaret Thatcher.

A reverse continuity can be traced from Britain’s New Wave of the late fifties, back to Free Cinema (1956 to 1958) and to SEQUENCE in the years after the War. The magazine was not particularly pro-British and certainly not political, but later developments were realist in style and implicitly (not explicitly) left-wing. Greatly to the disapproval of French-influenced “intellectuals”, they were also closely connected with the theatre, essentially the Royal Court, where John Osborne exploded in 1956, and with writers and actors. The common factor was not theory but intelligence. Tony Richardson was not at first an integral part of the critical movement, but he soon became connected with it. He contributed to Sight and Sound, collaborated with Karel Reisz on one of the first Free Cinema documentaries (Momma Don’t Allow) and was George Devine’s close associate in the early days of the English Stage Company at the Royal Court. Together Devine and he discovered Osborne, and Tony directed John’s plays and broke into feature production by founding (with John) Woodfall Films and turning Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer into films.

“No Film Can Be Too Personal”. So ran the initial pronouncement in the first Free Cinema manifesto. It could equally well have been the motto of SEQUENCE, for the editors were never interested in any judgement that differed from their own. Not that it implied any lack of social interest, for it was this that chiefly motivated the films of the British New Wave. (“Look at Britain” was the title that we chose for Free Cinema’s series of documentaries – which did not last long). After the Osborne films, Woodfall produced Karel Reisz’s phenomenally popular adaptation of Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, which superseded Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top with unglossy realism and the casting of two unknowns, Albert Finney and Rachel Roberts.

For a time it looked as though new directors, working-class writers and actors would disintegrate the bourgeois Establishment of British cinema. Karel’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, it is sometimes forgotten, derived immediately from his experience as a teacher and his Free Cinema documentary, We are the Lambeth Boys. He produced my Every Day Except Christmas (about Covent Garden Market) and also my first feature film, from David Storey’s This Sporting Life. Tony made A Taste of Honey and The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, and his Tom Jones (turned down by Balcon and Bryanston) became one of the most popular films, successful both at home and in the United States, ever made in Britain.

It did not last. The Rank Organisation had financed This Sporting Life, but it did not do particularly well and John Davis disliked it intensely. Rank, he announced would in future eschew such squalid and unreal material and return to the manufacture of “family entertainment”. (It was not long before Rank went out of production altogether). In 1967 Tony Richardson’s Charge of the Light Brigade, which combined the radical with the epic, was rejected by critics and public alike. The British cinema returned to its persistently middle-class ethos: themes of criticism and change were not welcomed. In the mid-sixties Ann Jellicoe’s moral comedy, The Knack, which had started at the Royal Court, was turned by Dick Lester into a crazy, amoral farce (produced by Woodfall, ironically enough). It won Grand Prix at Cannes and began the vogue for stories of Swingin’ London. The vogue petered out and in the early seventies the Americans, disillusioned and over-taxes, withdrew their money to California.

So ended the attempt to revitalise the British cinema which had begun with SEQUENCE. Tony Richardson shook the dust of England from his feet and became a resident of Los Angeles, not far from where Gavin Lambert, one of our initial editorial trio, was now living and working in Santa Monica. In 1973 Karel Reisz made his first American film, The Gambler, in New York. John Schlesinger, who had made his debut in 1961 with the North Country A Kind of Loving, made Midnight Cowboy, also in New York; and Joe Losey, the American exile who had become the favourite of the British critics, won great acclaim with the gracious subtleties of The Go-Between. Dick Lester followed The Knack with A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. The British lack of response to films which questioned the status quo was clear: “working-class” subjects were relegated to television, while radical and anarchistic habits were largely discarded. The tradition which had started with SEQUENCE came to an end.

So the British “New Wave” ended. How had it begun? To go back to those first years after the War must require a huge effort of readjustment. It cannot be easy for young or even middle-aged people today to imagine what life was like for the cinephil when the British Film Institute was decrepit rather than a profit-seeking bureaucracy; when there was no National Film Theatre and no National Film School; when the idea of owning your own videotaped copies of films by Griffith, Eisenstein, Ford, Renoir, Kurosawa and Ray (to mention no other great names of cinema) would have seemed outlandish fantasy.

During the last war, remember, many new films from Hollywood were never imported. Classics were hard to find. Books about cinema were scarce. There was Rotha’s very subjective “The Film Till Now”, erratic histories by Sadoul and Bardeche and Brassillac and of course those theoretical works by Eisenstein which decorated many intellectual shelves, largely unread and as little understood then as now. Roger Manvell’s “Film” was published by Pelican during the War and bought by everyone: it was an excellent “A.B.C.”. “Sight and Sound” was stodgy, and so was the “Penguin Film Review”, which Manvell edited. Film criticism was rare.

Much the same was true of film making. There were no television programmes to tell us how films were made, and when their new pictures appeared, film directors were never interviewed. We knew only that celluloid was inflammable, that meontage was made with a joiner, a razor blade and film cement that smelled of almonds; and that you mixed sound off film or gramophone records. If you wanted to record synchronised dialogue, you had to enclose the camera in a heavy, sound-proof ‘blimp’. If you shot a man at a lathe on the factory floor, or a woman out shopping. Both you and they would be distracted by cries from all around (I remember them in a broad Northern accent) of “Coom on, Clarke Gable!” or “Who d’you think you are – Greta Garbo?”

That was the cinema in 1946, when the Oxford University Film Society produced its magazine. It was edited by two undergraduates, Peter Ericsson from New College and John Boud from Jesus. They were enthusiastic, if ignorant. They promised development. When the next issue appeared, John Boud invented the title SEQUENCE; Peter executed a continuity of pen and ink drawings to decorate the cover. This was in December 1946, when I had been flown back from India (where I had struggled as a crypanalyst at the Wireless Experimental Centre outside Delhi) and joined the Film Society.

That summer I had visited Paris for a week with Gavin Lambert, who had been a school friend in my House at Cheltenham. We had started a film company there, more as a joke than anything else, which we called Parthenon Films. We collaborated on two scripts, one a thriller called Pursuit and one an adaptation of Madame Bovary, neither of which was produced. Gavin’s aunt was Claudine West, who was a scenarist at MGM; she was our Hollywood representative, though I don’t think she ever knew it. As a result of our film-going in Paris, I wrote a piece that was published in SEQUENCE ONE. I would not care to read it now; but it was a beginning.

Next year the Society published SEQUENCE TWO. This looked more or less as the magazine would look later: on the cover was a still from My Darling Clementine. Here was another step forward. By 1947 Peter Ericsson and I had both fallen under the spell of the poet Ford. We had seen My Darling Clementine several times and, and found it greatly superior – even as we struggled to understand exactly why – to the British films of Lean, Reed and Powell then being hailed and lauded by the press. (The “Times” reviewer consigned Clementine, which was set in Tombstone, to “the graveyard of mediocrity”). So the first of our relatively long articles on a director, which were to become the centrepiece of the magazine, was devoted to John Ford.

In 1948 SEQUENCE came to London and announced in an editorial that it had started its career as a quarterly. The Film Society committee gave Peter and myself permission to remove the magazine from Oxford (they also paid the outstanding bills) and I asked Gavin Lambert to contribute a study of the films of Marcel Carne. The university tradition persisted: Gavin had been at Magdalen for a while, where he had assisted Peter Brook on his first film A Sentimental Journey. Our co-editor on SEQUENCE THREE was Penelope Houston (Sommerville) who could write about anything with amazing confidence. On the next issue, Gavin joined Peter and myself to form an editorial trio. Of course we were never really a quarterly, though we did our best to publish regularly. With equal fantasy we announced that we welcomed contributions “from anyone, on any aspect of the cinema, written from any point of view”. This was never true. SEQUENCE was almost entirely written by its editors, with some help from friends. Pseudonyms were taken from characters in films (“Alberta Marlow” was played by Mary Astor in Across the Pacific). We were never interested in any judgements or ideas that differed from our own. No one was paid.

Why, you may wonder, did SEQUENCE exist? There is surely a great difference between our enthusiasm then, and the ambition that inspires young people forty years later. We were not careerists. We had no desire to establish ourselves as journalists or even as film makers. We were certainly not doing it for profit. But it seemed important to say what we thought and felt. Right opinions should be heard. We were, in fact, an odd trio. Gavin wrote scripts for Rank Advertising and worked on his own stories. I had started making publicity films about belt conveyors for Richard Sutcliffe Limited of Horbury, Wakefield. Peter had a mysterious job with the Foreign Office, spoke Russian, German and French. He sensibly balanced our enthusiasms. We were each individual, but on fundamentals we did not disagree. We trusted each other.

As publishers we were amateurs. We typed the copy, measured column inches and ems to calculate the size of columns and the numbers of words on a page. Stills had to be measured (you draw a diagonal across the back) so that blocks could be made. And pictures had to be obtained by fair means or foul. Many were the visits we paid to Wardour Street distributors, purloining stills from filing cabinets, hiding them in brief cases and under sweaters. And many were our friends and sympathisers: Lois Sutcliffe, who started me off as a film maker and sold SEQUENCE in Wakefield. The cheerful publicist at MGM who later turned into a woman. Contributors like Satyajit Ray, Douglas Slocome, Catherine de la Roche. Everyone (listed in our last number) who helped buy blocks for SEQUENCE FOURTEEN. Walter Lassally and John Fletcher who helped make up parcels and became fellow film-makers. Stella Paterson and Irene Philips, staunch helpers. Friendly critics: Dilys Powell, George Stonier, Richard Winnington. Alex Jacobs, first encountered at UA, who rode in bicycle races, later helped to publicise Free Cinema and went to Hollywood as a writer, where he died of cancer . . .

We had good fun doing SEQUENCE: its impertinences still make me laugh. Also Peter’s drawings. Most importantly, we took moral relevance for granted: we did not value artistic or stylistic achievement for itself alone. (This was a traditional principle, not to prove long-lasting). Then in 1950 Gavin moved on, invited by Denis Forman to his revitalised Institute, to edit “Sight and Sound” – from which Michael Balcon did his best to get him fired, because he had dared say rude things about “The Blue Lamp”. Earlier, I had been lucky enough to meet Karel Reisz, when we were double-booked on to the National Film Archive Movieola at Aston Clinton. I was researching Hitchcock and he was viewing Mata Hari for his book on film editing; so we watched each others films. That was a lucky clash, for Karel became a SEQUENCE critic and helped me to edit the final number. This, of course, was quite apart from the contribution he later made to Free Cinema, and my debt to him as my producer.

Forty years on, it is probably best to let SEQUENCE speak for itself, always supposing it speaks at all. But there are two if its characteristics that perhaps call for comment. In view of developments to come, it may seem surprising that we had so little care for Documentary. But our concentration on feature films, and later on feature film making, was not simply negative. The British documentarists never seemed to us to be very concerned with the life around us (“The poetry of the everyday”, as the Free Cinema Manifesto put it). John Grierson himself, though a great producer, was more interested in social propaganda than art. This did not appeal to us.

And anyway the great period of Griersonian Documentary came to an end with the War. Nothing much was said about post-war Britain by the Shell Film Unit and Three Dawns to Sydney. We warmly admired the achievements of Humphrey Jennings, but we had as little sympathy with Grierson and his surviving disciples and they (on the whole) had with us. Arthur Elton reviewed Every Day Except Christmas most unfavourably in the Union “Journal”, remarking on my failure to raise the issue of strikes in Covent Garden and comparing my affection for my characters with Noel Coward’s farewell to his ship’s crew in In Which We Serve. And I remember meeting John Grierson at Beaconsfield, in the tentative pursuit of a job with Group Three. I was received without warmth, but Grierson spoke glowingly of the Group’s record. “We have a director shooting now who may well turn out to be the British Rene Clair,” he told me. The picture was Miss Robin Hood, starring Margaret Rutherford, and the director was John Guillermin.

Equally remarkable, looking ahead to the New Wave, must be the lack of interest SEQUENCE showed in the British cinema generally. By the end of the War, British films were respectable and overpraised. They had made their contribution to the mood of national self-confidence. They reflected the class divisions of the country faithfully enough: working-class comedies to divert the popular audience (George Formby, Gracie Fields, the Crazy Gang), with ‘serious’ cinema remaining a bourgeois preserve. The industry remained a closed shop. BBC Television still wore the Reithian collar-and-tie, while commercial television did not yet exist. Film makers were defended by their unfriendly and philistine union. When I wrote of British production as ‘The Descending Spiral’ and poked fun at Ealing’s Scott of the Antartic (“The Frozen Limit”, Gavin captioned it) I was referring sarcastically to a piece by George Stonier for Vogue, titled “British Cinema: the Ascending Spiral”. Why should we join in the chorus of praise? It was much more useful, surely, to draw attention to the vision and vitality of American cinema – then much despised. Things would change, of course.

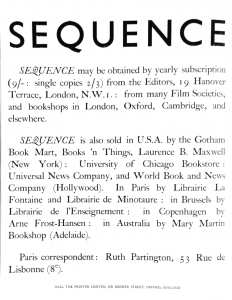

With these attitudes, there was no way that SEQUENCE could survive for very long. We had no backing and, at our peak, we only printed five thousand copies. Costs, it is true, were relatively low in those days, but we paid them ourselves with a loan generously, if inadvisably, made by the photographer Anthony Panting. (How we grew to dread those telephone calls, asking so mildly for repayment. In vain.) The magazine was not widely popular. Perhaps it was too “specialised”. We certainly never had the slightest acknowledgement from, or effect on, the British film industry. We gave some parties, and even film makers turned up to drink and talk at 19 Hanover Terrace Mews, but only the Mackendricks and the Dicksons asked us back.

Other magazines, other critical tides have flooded in over the last forty years, mostly proving the rightness of George Orwell when he noted the tendency of English intellectuals to look abroad for their ideas about art. SEQUENCE though was quite untouched by French influence and the aesthetics of “Cahiers du Cinema”. We certainly had no time for the auteur theory. From the start we knew that the film director was the essential artist of cinema; but we also knew that films have to be written, designed, acted, photographed, edited and given sound. We tried to look for the creative elements.

Inevitably, however, criticism has followed history. Film Appreciation, that horrible “discipline” which has acquired academic status over these forty years, still borrows its aesthetics from Europe. Journalists speak popularly with the voice of America. Money talks; and money comes from across the Atlantic. The British have never considered a national cinema (since the War that is) of any importance. No British artist is featured on the wall of portraits displayed outside our Museum of the Moving Image. Every month the covers of British magazines are more regularly devoted to portraits of Kevin Costner, Michelle Pfreiffer, Robert de Niro, Meryl Streep. And each year the prizes awarded to film makers by Hollywood technicians and artists occupy more space in the British press; Barry Norman is flown to Los Angeles to report on the Oscar ceremony for British television. The tradition of independence and intelligence, of wit and style, which we tried to uphold in SEQUENCE has been overwhelmed by the persisting accents of Oxbridge, the bully-boy vulgarities (American accented) of Redbrick, the bloodless theorising of Film Departments.

In 1991 the National Film Theatre (whose new Programme Officer was American) presented a series of programmes under the title “Images”. M Raymond Bellour, the visiting British Film Institute “Research Fellow”, introduced this season with a bold pronouncement.

“What is really new is the extraordinary acceleration of the effects of mixing which contaminates every use of the image, which can no longer be understood independently of television or the computer. Thus in the cinema we have entered a new period, a new physics of the image.”

Alas there is no SEQUENCE around any more to dismiss this stuff with the healthy derision it deserves.

LINDSAY ANDERSON

30th March 1991